A recent opinion piece in the Menagerie section of the NYTimes got me thinking about my history and beginnings with animals. As I work through the long marathon of my dissertation research, analyzing and writing up data on a daily basis, I’m reminded that my work is largely a result of my earlier experiences and disillusionment working around animals in various settings. The piece is a well-written reflection that stirred a number of memories about my own animal adventures–some happy, some sad. I had held a number of internships working with animals in college and had traveled to the opposite end of the globe to study bats in Australia, but my biggest enterprise came straight out of college with a position as the primate research assistant for the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund at Zoo Atlanta. Whatever preconceived notions or romanticism I held about the job were quickly dissolved within the first few weeks of my position. Fresh from Swarthmore, I moved away from all of my friends in the Philly area within a week of graduating and arrived in a city where I knew only a couple people. Perhaps that’s why my work around the animals became all the more important. Suddenly, making friends was not as simple as stumbling out of your dorm room into the hallway where all of your best friends would congregate to play cards. So, I eased my Swat-sickness and perplexed feelings at being an adult in the real world by focusing on the animals with whom I was working. I assumed I would figure out the friend thing and orient myself to Atlanta eventually, so I did what I always do in times of adjustment; I spent time around the animals.

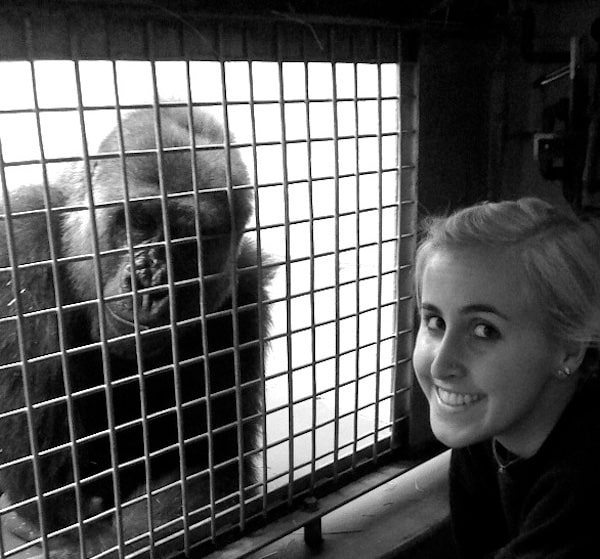

Olympia and I

My work was nothing like the jobs my friends were starting. While they wore suits and dressed nicely, I had a rotating slew of khakis and a navy Zoo Atlanta t-shirt that I had to wash almost daily due to the gnarly realities of animal scat slung my way. Having become accustomed–and somewhat of a connoisseur–of animal scat through my earlier work (did you know you can use hyena poo as chalk because it consists largely of digested bone?), I remained unfazed by the muck. It was a small price to pay for the daily company I received in my various projects behind the scenes of the zoo. While guests would come and watch the gorillas or orangutans from the comfort of the air-conditioned primate house, I would sit up on the roof and carry out observations on the various gorilla family groups. I would watch as the baby twins would play in a hose’s mist, cupping their hands and emitting happy grunts. I envied them because I was sitting on a black tarmac that radiated heat in the Hotlanta sun. I came to know these gorillas quite well over the course of my year, spending hours watching them each week to study their behavior using an ethogram my boss had designed. In between the stopwatch beeps for me to take a scan sample, I would study their faces and try to imagine what they were thinking. Is Taz annoyed by little Kali clapping at him for attention? Is Olympia going to try and disable the hotwire again? Is Ozzie judging me while he sits there staring back at me—this pale sweaty mess of a girl sitting on an old crate doing nothing but writing?

I adored the gorillas, but my favorite time of the day was in the morning, which I spent in the orangutan nighthouse. There was one family group in particular that I found myself increasingly connected to. Much like the author of the Opinionator piece, I felt like I could relate to the curious and somewhat awkward group. The baby, whom I called little D, was a troublemaking three-year-old who consequently just discovered his ability to harass his adopted father and mother. I would be trying to carry out a project, and Little D would derail whatever I was doing with his mom Dewey or dad Chantek. His wiry figure, probably no more than a foot, was surprisingly strong and could propel him up and down the mesh of the nighthouse. I sat on the other side, dodging his attempts to spit at me or throw stuff at me for my attention. I’m an only child, so I totally get his need for that. I would sing to him or tell him to wait patiently while I finished my work with his parents. His birth mom died when he was only a few months old, so they brought little D to the zoo where Dewey then took him on as her own–not a common thing, and a remarkable testament to Dewey.

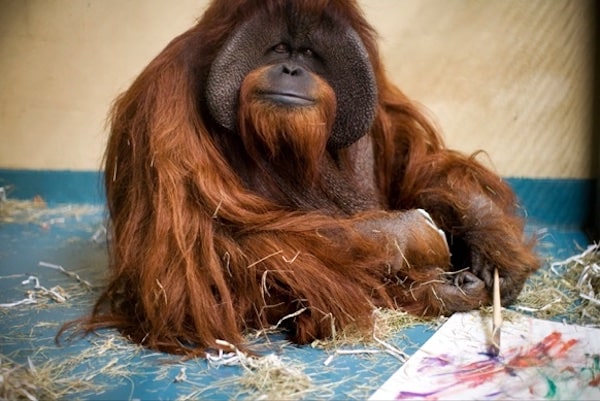

Dewey

Little D’s ‘father,’ Chantek, was perhaps my favorite of all. From the beginning, he was the best part of my day. I had to carry out cognitive research projects with him, which required me to set up a touchscreen computer for him to play matching games on. This device, in order to withstand the strength of an adult male orangutan, weighed twice as much as I did. So, to move it in the mornings, I would have to jump on the cart and wheel it over to Chantek without knocking the multi-thousand dollar device over and crushing myself. I’m sure this amused Chantek because he would sit there, knowing what I was trying to do and waiting patiently to ‘work.’ I should add, Chantek knows sign language, so he had no problem making editorial comments as I struggled to move this cart around each day. His nickname for me? White Sugar–because I always carried ‘candy’ in my pockets for his matching games. It wasn’t candy though; captive animals are already at risk for obesity due to the more sedentary lives they lead compared to the wild. The treats were actually an orangutan version of Flintstone vitamins that I would give to Channy whenever he got a match correct. I treasured those mornings with Channy because I felt like I could relate to him. An animal’s eyes are the fastest way to make a connection with them, and I would stare at him and he would stare back, making us terribly unproductive but a little less alone.

Chantek and Little D (*Photo Credits go the the Zoo Atlanta keepers for these).

At this time, I was wrestling with the uncertainty that comes with being a recent college graduate. Suddenly, nothing was straightforward and the decisions you made felt like they carried a heavier weight to them. Asking yourself seriously, what do I want? What comes next? It all was no longer as simple as: after middle school comes high school, and after that college. So, um, what was next? I thought this job would reiterate that I was supposed to be a veterinarian or an animal behaviorist who studies cognition. Instead, it totally disrupted my ideas and left me questioning some of the structures that exist in animal management. I’ve always felt conflicted about zoos, and here I was working within one and witnessing things that left me less than pleased. I couldn’t in good conscience just stay on the path that I was on, so I spent a lot of that year thinking of another route I could follow that felt more authentic and in line with my unflinching quest to make room for wild things in our world. This thinking often left me frustrated, so my reprieve was in the mornings with Chantek. We would sign back and forth, him doing a better job than my struggles with the ASL alphabet. He often asked for food or to see what jewelry I had on, and he was always quick to show me something on his arm or neck that he wanted me to see. When I would lean in and blow kisses at him on my side of the mesh, he would emit a low rolling rumble that echoed around the nighthouse. On days where there was construction going on, he would be agitated and distracted, not liking men in his territory. The docile Channy I knew would instead show off his staggering strength by picking up a truck tire (that took three men to carry) and launching across his nighthouse. I was reminded in those moments of his animality. I know enough about that to always be careful. I make no illusions that wild animals are still, at heart, wild animals. They are not domestic creatures for us to treat as pets, children, or loved ones. I remain furious at any person who asks me if I would want a monkey, ape, or any wild animal as a pet, because that is more disrespectful than anything I could think of. I have too much respect for wild animals, and it’s hard enough to retain that wildness in a zoo setting. I should add, I remain cautious in my descriptions and narratives of Chantek, because I know all to well the dangers of anthropomorphizing animals. Like Darwin’s Theory of Common Descent, I adhere to an ontology that appreciates our differences and similarities with animals as a matter of degree, not kind. Far be it from me to ever expect Channy to be mine to construct or tell what to do. Channy was so much more than a research object; he was my friend. He was a constant each day when everything else felt big and scary.

One day sticks out the most in my mind with him. I was in a bad mood because I had cut myself like the klutz that I am, and I had a huge bandage wrapped around my hand. I was running late to go work with Channy, which put me in an even worse mood. When I finally got to his nighthouse, I was uninterested in deciphering what Chantek kept trying to tell me. Finally, I stopped setting up the computer and snapped, ‘What, what is it you want to tell me?’ And he was signing to say he was sad. Still impatient, I said, ‘Sad? Chantek, why, why are you sad? We need to work.’ He signed back to me, ‘I’m sad because you’re hurt.’ I’m pretty sure that was the most humbling thing that’s ever happened to me. First of all, I felt terrible because I was no better than the people I criticize for expecting an animal to work on my agenda. Chantek is his own being, with his own feelings, and he was curious and concerned enough to tell me he cared, in his own way. Second, I knew then that I didn’t want to be someone who tallies behavior to look at whether or not animals have empathy. There is great research being done on empathy in primates, but I don’t need to be another person studying that because I had the best example of it right in front of me. I know enough about psychology to know that empathy comes through relationships and time-deepened personal encounters with someone. Here I was, in my own selfish world being reminded that it’s not all about me. Being the emotional mush that I am, I started to cry and felt terrible for being so rude to my closest friend in that place. I apologized, and I spent the rest of the morning just sitting with him. Work would have to wait that day, and I didn’t really care about getting in trouble because what I needed most that day was to slow down.

I still credit a lot of my current research and thinking to the ups and downs of my first post-college job, but I think most of that credit belongs to Chantek. I’ve always thought animals deserve their own recognition in the conversations about how they should be managed, and actually getting to know them on an individual level (though difficult and demanding) only served to underline that for me. Being a master at reading body language, Chantek was somewhat sullen on my last day at the zoo. I had gotten special permission from the curator to paint with Chantek, my present for finishing the one-year position. I brought in glass ornaments, and the keepers devised a special paintbrush made out of pvc-piping and horsetail hair that could go through the mesh. I brought out the cups of paint, and I asked Channy to pick out his colors. He would point, with his large brown fingers that were three times the length of my own, and I would hold up the cup for him to dip the brush in. With a delicate touch unexpected for an animal of his strength, Channy then gingerly painted little swipes of color on the glass ornaments I was holding up for him. I did my best not to cry afterwards, feeling a mixture of guilt for leaving Chantek while I went on to my next enterprise of grad school as well as sadness. Sadness over the fact that I would no longer get to see someone who made an otherwise unfamiliar process of young adulthood a little less daunting. Those ornaments now sit above the windows in the small living room of my apartment in Queens. I keep them up year round, so I can think of my friend whenever I see them and feel a little stronger whenever I’m intimidated by the work I’ve chosen to do.

Artist in Residence.